Ōtorohanga Friendship Club president Trish Neal, left, with Judge Coral Shaw. Photo: Viv Posselt

Pirongia-based Judge Coral Shaw, who was made a Dame Companion of the New Zealand Order of Merit in the New Year Honours, says she will use the accolade as an opportunity to continue to be a voice for survivors of systemic abuse in state and church institutions.

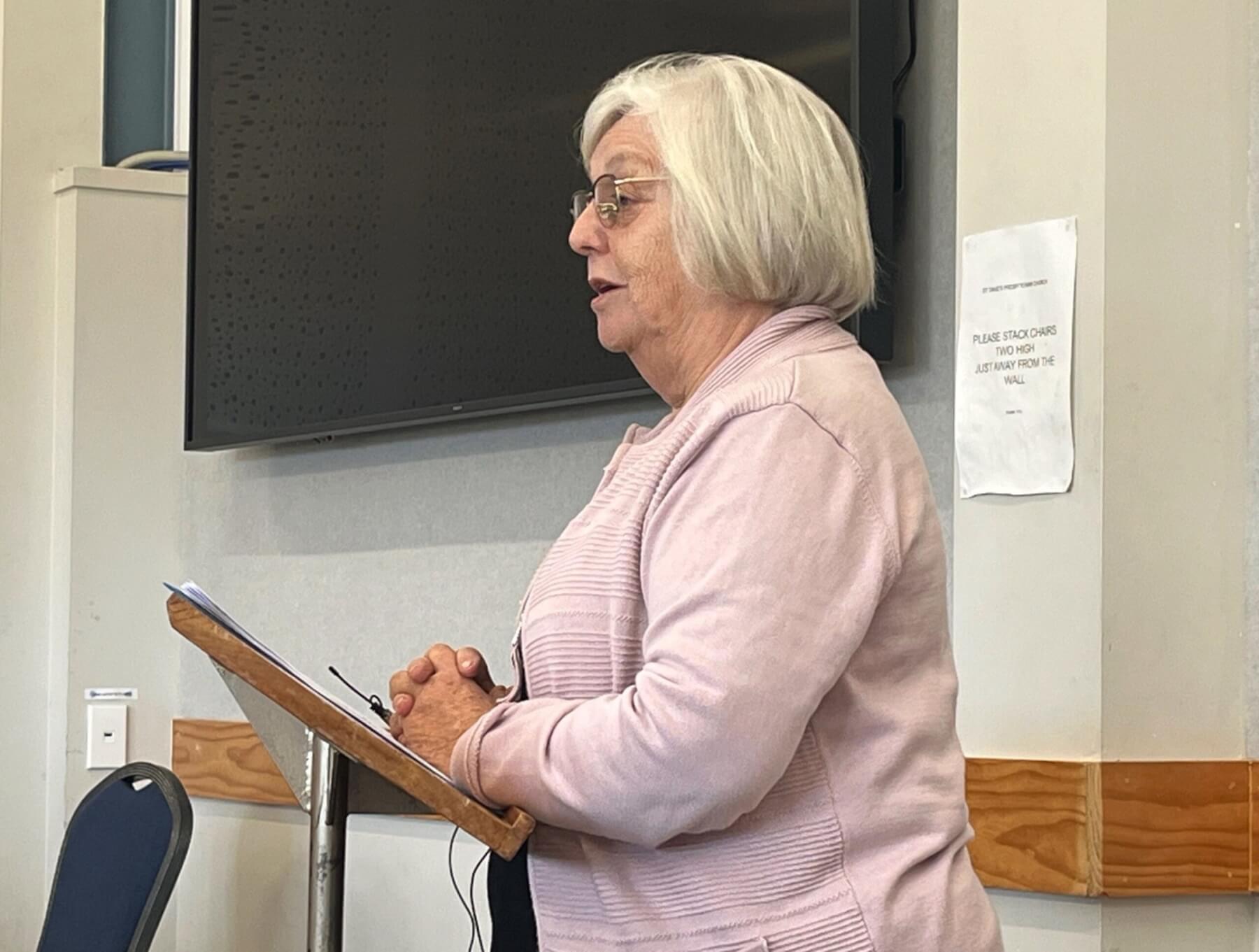

Judge Coral Shaw speaking to the Ōtorohanga Friendship Club last July. Photo: Viv Posselt

Shaw received the honour for services to public service, the judiciary and the community. She chaired what became the largest and most expensive inquiry in New Zealand’s history – the Royal Commission of Inquiry into historical abuse in state and faith-based institutions.

The inquiry was established in 2018 to investigate what happened to children, young people and vulnerable adults in care between 1950 and 1999. Its final report, entitled ‘Whanaketia – through pain and trauma, from darkness to light’, was tabled in Parliament on July 24, 2024, and made public the same day. It had been delivered to New Zealand’s Governor-General Dame Cindy Kiro in June 2024.

Coral Shaw

Shaw told The News she appreciates the recognition awarded through the New Year’s honour and is grateful for the opportunity it presents to continue advocating for survivors of what she described as New Zealand’s ‘national disgrace’.

“This is not for me; it is for the cause. I am grateful for the opportunity it provides to apply pressure and keep the issue in the public eye,” she said. “People assume that the problem ended when the inquiry did, but in reality, the findings we took to government were just the beginning. I will use this honour as another opportunity to be a voice for survivors and for those who are still suffering abuse.”

Shaw has spoken on the issue several times at conferences both in New Zealand and in Australia. Central to her message is ‘what next?’.

“Our inquiry found the abuse was not simply bad stuff done by a few bad people. It was systemic throughout those institutions… the evidence was overwhelming. Our report called for fundamental changes.”

She said while some institutions have tackled the problem from within, a key recommendation had been for government to lead, oversee, set standards and monitor the changes enacted by the institutions themselves.

“I am disappointed in the slowness of the response. The inquiry was not the end, it was the beginning… less than 40 per cent of the recommendations have been accepted so far, and the rest are still being considered.”

Aside from the human toll, Shaw said the economic cost to society was massive. In 2019, the average lifetime cost for an individual abused in care was estimated to be about $857,000. Of that, about $184,000 was increased spending on healthcare, State costs around negative outcomes from abused children, deadweight losses from collecting taxes to fund State services, and productivity losses. The remaining $673,000 is a non-financial cost reflecting the pain, suffering and premature death of survivors, and the impact on their quality of life.

Shaw said there was a general perception that the problem had gone away, but it has not.

“We still get reports of abuse, and there continues to be a disappointing number of Māori children who are being uplifted. Part of our recommendation was to attack the root causes that lead to that situation… alienation, racism. To save the child, you first save the family.

“We have to keep the pressure up, keep talking about this,” she said. “We would like to see all the necessary protections in place by 2040. That is not unreasonable, but it will happen only if we continue to recognise ongoing abuse and keep talking about it.”

Judge Coral Shaw flanked by Ōtorohanga Friendship Club president Trish Neal, left, and club secretary Catherine Short. Photo: Viv Posselt