Ōtorohanga Friendship Club president Trish Neal, left, with Judge Coral Shaw after the meeting

The spectre of abuse in some New Zealand care institutions will remain unless those responsible are held accountable and a bipartisan government approach is taken to address the recommendations of the Royal Commission of Inquiry into historic abuse in state and faith-based Institutions.

Judge Coral Shaw flanked by Ōtorohanga Friendship Club president Trish Neal, left, and club secretary Catherine Short. Photo: Viv Posselt

This was said last week by Judge Coral Shaw, who chaired what became the largest and most expensive Inquiry in New Zealand’s history. Established in 2018 to investigate what happened to children, young people and vulnerable adults in care between 1950 and 1999, the Inquiry finally ended last year. Its 139 recommendations were delivered to Internal Affairs Minister Brooke van Velden in May 2024.

Speaking to members of the Ōtorohanga Friendship Club, Shaw outlined the ‘staggering scale’ of the Inquiry, its findings revealing decades of sustained horrors, systemic failures, cover-ups and deflections. Many of those responsible for the abuse were never held accountable, she said, others had enjoyed the wider institutional cover-up of their crimes while some had gone on to fulfil similar roles abroad.

“I have no confidence that such events will not occur again,” she said. “Most of us are just one or two degrees away from the tragedy. We need to know and recognise that it was not a case of a few bad people working in good institutions but rather it was the institutions themselves that hid the violence and neglect, thus attracting the bad people to work in them.”

Shaw, who as a district court judge in Auckland introduced a first fast-track system for family violence cases, also served as a judge of the New Zealand Employment Court and a judge of the United Nations Dispute Tribunal. She was appointed to oversee the Royal Commission into abuse in 2019, taking over from Sir Anand Satyanand. She lives in Pirongia.

She spoke of being ‘haunted’ still by the face of a young woman who brought to the then new lawyer her own harrowing story of abuse in state care. Shaw reached out for information but couldn’t trace anything on the woman. The case faded away. It was her first brush with the mechanisms put in place to hide information and shield the perpetrators.

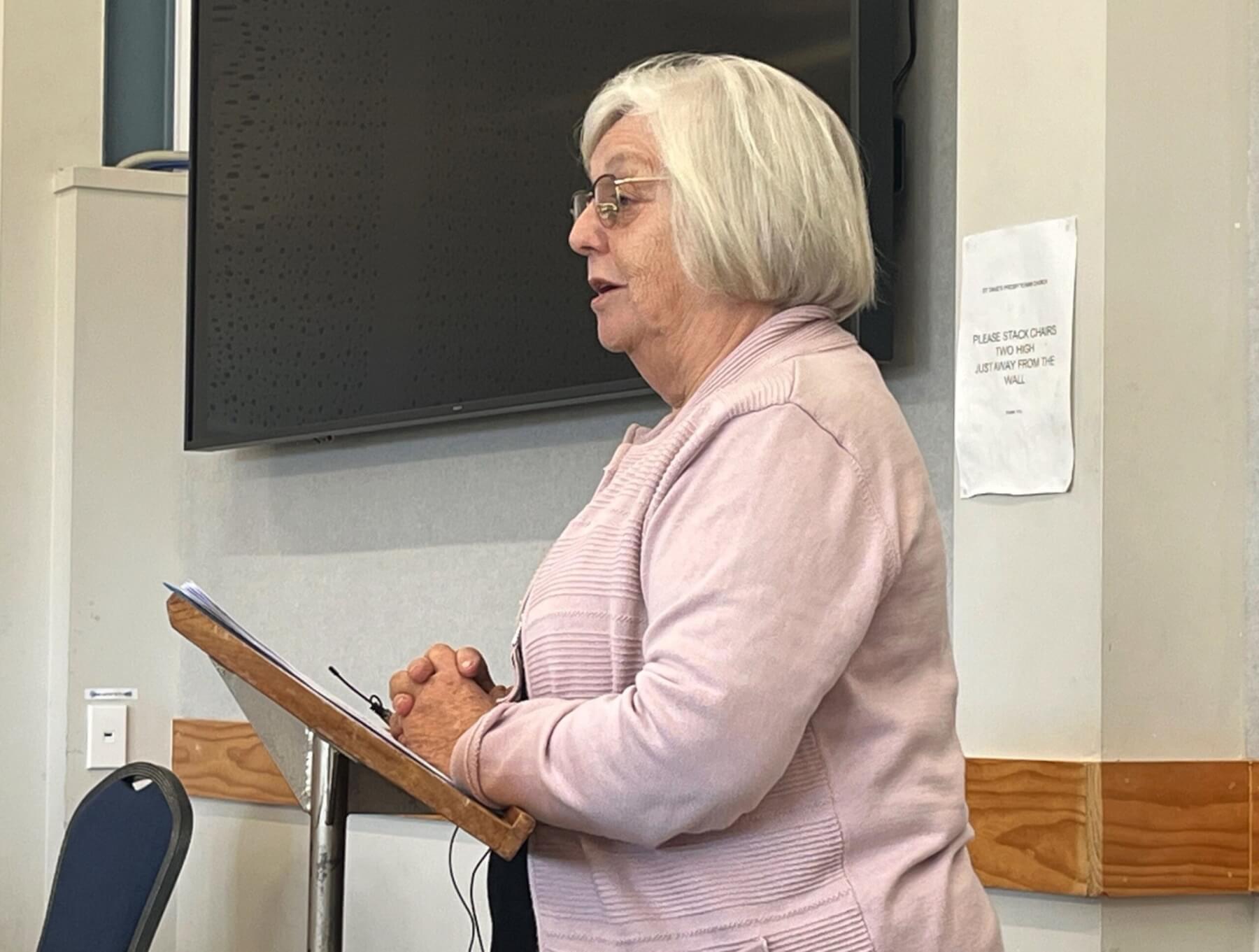

Judge Coral Shaw speaking to the Ōtorohanga Friendship Club last week. Photo: Viv Posselt

During the almost six-year Inquiry, Shaw presided over four commissioners and teams involving some 300 lawyers, researchers, policy analysts, experts and more. Over a million documents were gathered from faith-based institutions.

“The scale was staggering. We estimated that from 1950 to 2019 about 655,000 people were in care, and of these 256,000 (well over a quarter) were abused or neglected – an indelible stain on the nation’s conscience,” she said. “We conducted 13 public hearings and countless private sessions, where survivors spoke with raw courage about the trauma they lived with.”

Some 64 per cent were Pākehā, 44 per cent Māori and five per cent Pacifica. Shaw said the imbalance in the number of Māori represented was disturbing given that at its peak they were 20 per cent of the population.

With the final report, the Inquiry delivered seven case studies that focused on particular institutions where people had been abused. They were the Hokio Beach and Kohitere Boys’ Training Centre (a case study of the state’s role in creating gangs and criminals); the Kimberley Centre (an institution for people with learning disabilities); Van Asch College and Kelston School for the Deaf; Boot Camp – Te Whakapakari Youth Programme; Jehovah’s Witnesses; the Order of the Brothers of St John of God at Marylands School and Hebron Trust; and the Lake Alice Child and Adolescent Unit.

An imbalance of power within institutions and a fear-based reluctance of bystanders to report incidences was key to much of the abuse remaining hidden.

“Our findings were unequivocal and quite horrible,” Shaw said. “State and faith-based institutions were entrusted to care for many children, young people and vulnerable adults. New Zealanders held the leaders of those institutions in high esteem. They had a duty to care for people and help them flourish … they failed. Instead, those in their care were exposed to physical, mental and sexual abuse and severe neglect. The true number of those abused with never be fully known as records were never kept or were destroyed.

“This gross violation occurred at the same time as Aotearoa New Zealand held itself up as a bastion of human rights. If this injustice is not addressed, it will remain a stain on our national character for ever.”

Ōtorohanga Friendship Club president Trish Neal, left, with Judge Coral Shaw after the meeting. Photo: Viv Posselt