Volcanic eruption

This week in The New York Times is an article titled “Volcanic Eruption in Deep Ocean Ridge Is Witnessed by Scientists for the First Time.”

Isn’t that amazing — that we can be witnessing one of Earth’s fundamental processes for the first time in 2025?

The researchers were using a submersible to study an area over 2000km offshore from Costa Rica, in the eastern Pacific Ocean. One day, they were observing an incredible ecosystem 2.5 km below the ocean surface near a hydrothermal vent. When they returned the next day, the seafloor was black and lifeless.

Above the fresh lava — quickly quenched into solid rock — were particles suspended in the water, and they even saw hints of molten lava. They were witnessing the end of the eruption.

You may have heard it said that we know more about the surface of the Moon than we do about our deep oceans. Here on the North Island, we can get to the beach within a few hours’ drive and dip our feet in the ocean, while the Moon is 384,400 km away.

We’ve used satellites to map the Moon, landed rovers on its surface, and even brought back samples that have been studied in detail. The lunar surface has been thoroughly mapped and continues to be researched.

In contrast, people are working to map the entire seabed by 2030 — an international collaboration aptly named Seabed 2030. According to the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, as of June 2024, only 26.1 per cent of the seabed had been mapped using high-resolution multibeam sonar technology.

Considering about 70 per cent of our planet is covered by oceans, which leaves an enormous area still largely unexplored. There’s so much left to discover — so many exciting breakthroughs in knowledge and understanding still to come.

We have a general map of the seafloor based on satellite altimetry, which measures variations in sea surface height caused by gravitational influences from the seafloor. While this provides a decent broad view, it lacks detail.

That said, we do know quite a bit. We know where tectonic plates collide and pull apart, where major fault zones create trenches and ridges. And as our technology advances, so too does our understanding of what lies beneath.

We don’t know how many volcanoes are hidden beneath the sea surface. In 2011 more than 24,000 were estimated, and in 2023 a study identified another 19,325. These features were classified as “smaller seamounts,” meaning they were less than 2.5 km tall — still far from “wee little hills.”

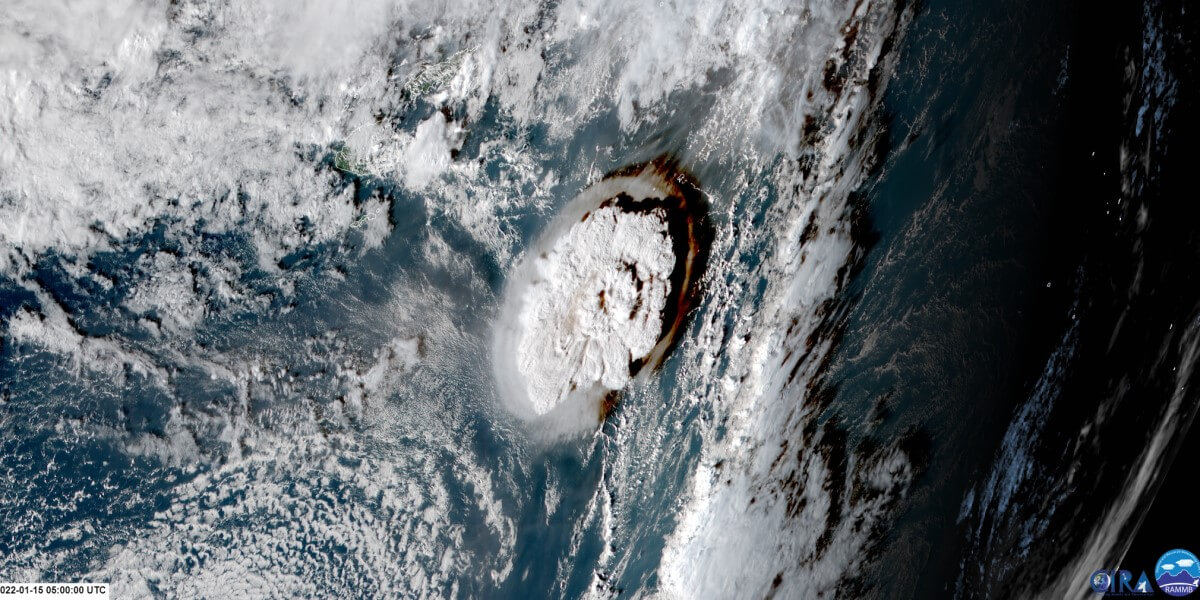

Our record of eruptions on land shows a steady increase since 1800, but today we can detect most surface eruptions even when no one is there to report them, thanks to satellites and global monitoring systems.

I hope this sparks a sense of inspiration and awe, knowing there’s so much beauty left to discover on our planet — and so much exciting work still to be done to understand it. Who knows where our technology and curiosity will take us next?