Janine Krippner

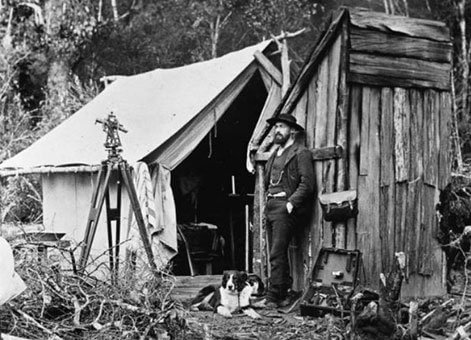

Early in the morning of 10 June 1886, surveyor John Rochfort in Kihikihi experienced a bizarre show on the horizon beyond Maungatautari.

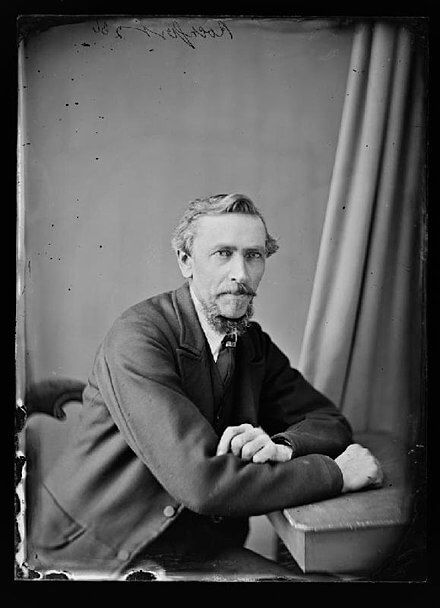

John Rochfort, circa 1870s. Photo: Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand.

“I was awakened by what sounded like an irregular discharge of artillery… I went outside to try to discovery the cause, and watched for about two hours what appeared to be a splendid electrical storm… intermittent flashes of sheet lightning played, while at short intervals balls of fire shot up…”

Along with many others in the North Island, Rochfort was witnessing the Tarawera eruption. Explanations for what people were seeing, feeling, and hearing varied as people were woken by what sounded like cannon fire. People from Auckland all the way to Christchurch tried to make sense of hearing distant explosions in the early hours. Residents in Blenheim were woken by “sharp and regularly repeated reports”.

Those in Wellington thought they could hear thunder and could see distant lightning. In the Manawatu region, one thought their neighbour’s horses were trying to kick their way out of stables. Another thought burglars were trying to steal his safe, and someone else thought the noise originated from a “lunatic confined in the police cells”.

In Whanganui and Kawhia, people went out to try to locate what sounded like a ship in distress. Many around the island thought the Russians were attacking, as a man-of-war ship Vestnik just so happened to be nearby.

Ash smelling of sulphur fell at Whakatane and Tauranga.

Closer to Tarawera the stories get more harrowing, triggering goosebumps as I read them. Reactions ranged from confusion and awe to sheer terror as people grappled with the ground below them shaking, an eruption opening up across Tarawera, then material falling from the sky with a backdrop of intense lightning and “fire” (lava).

These people were experiencing a very violent type of eruption and the most destructive in our recent history. A 17-km-long fissure opened up along Tarawera and through what is now Lake Rotomahana and the Waimangu volcanic valley.

Dozens of vents were active over around 4 hours, some violently ejecting lava and ash high up into the air, while others produced a deadly, steam-rich pyroclastic surge. Vents opened below the lakes containing the Pink and White Terraces, coating the area with lake sediments now known as the Rotomahana mud. This heavy, thick mud collapsed homes and caused the landscape to be difficult to cross during the search for survivors.

The numbers are unclear, but around 120 souls lost their lives.

To think of much of the country today being woken by the sounds and sights of this exceptionally explosive eruption is harrowing.

Could we be woken up by a large eruption? Yes. When and where will it happen? We don’t know.

The impacts would be much, much greater today, with a larger population and our modern infrastructure.

Thanks to Ronald Keam arranging these accounts in his 1988 book ‘Tarawera’ we have an extensive record of that time. It’s our job to make sure we are prepared for when it’s our turn. We are not powerless.

See: The story of John Rochfort

John Rochfort